On March 4, 1960, at 6:43 p.m. local time, residents of a certain town, specifically those on Maple Street, saw a bright flash in the sky and heard a strange noise. They thought it might have been a meteor. But after the lights went out and cars wouldn’t start, and after a serious-minded teenager suggested that aliens were responsible — aliens disguised as humans! — the neighborhood quickly descended into paranoia, mayhem, and murder.

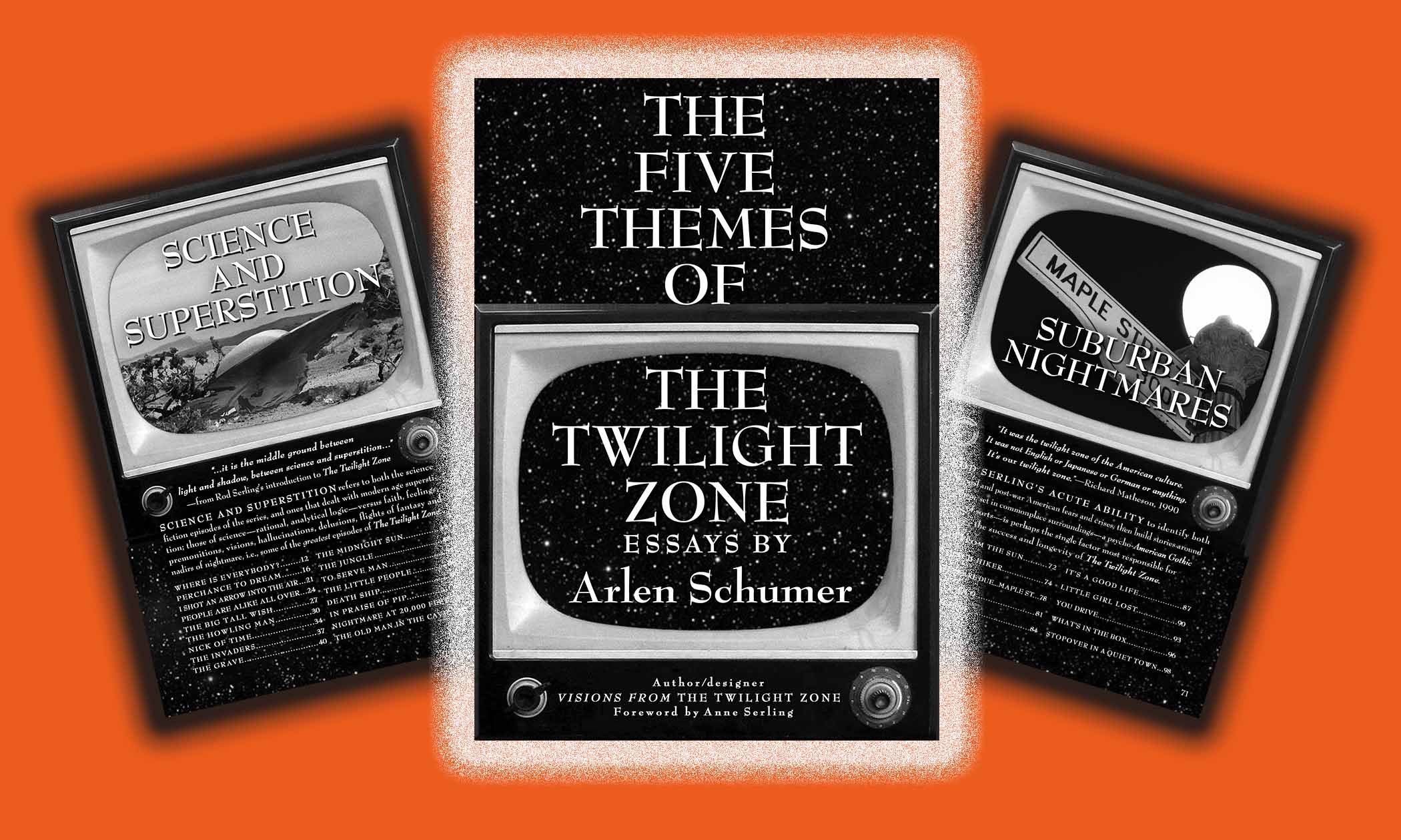

If that event sounds familiar and your brain is now repeating a dissonant four-note tune, you might be as big an aficionado of The Twilight Zone as author and illustrator Arlen Schumer, who declares in his new book, The Five Themes of the Twilight Zone, that the show is “the greatest television series of all time.” Of course we’re talking about the original version, the Rod Serling brainchild that first aired on October 2, 1959, on CBS, and ran for five seasons, making its fable-like plots, that spooky theme, and Serling’s distinctive narration into emblems of the weird, the mysterious, and the unnerving.

The book’s title smacks of an academic monograph, but Schumer has written an easygoing — if effusive and occasionally overstated — guide to the show’s historical, artistic, and cultural significance. It feels timely. Sixty years after going off the air, The Twilight Zone might be more relevant than it was at the height of the Cold War. Or, more accurately, the world might be more relevant to the show.

Let’s return to that scene of paranoia — episode No. 22 of The Twilight Zone’s first season, “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street.” In the last-minute plot twist — the show’s trademark — the camera pulls back from the town, now engulfed in mob violence, to reveal two aliens monitoring the mayhem, having engineered it all themselves as part of their plan to take over the Earth. “All we have to do,” says one, bragging about their easy manipulation of Maple Street, “is sit back and watch.”

In its day, the episode would have signaled the dangers of McCarthyism. Decades later, it comes across as a lampoon of the MAGA cult — a mob easily manipulated by a conspiracy-minded duo who sit back and watch.

Serling’s introductory narration for that first season defined the “twilight zone” as “a dimension that lies between light and shadow, between science and superstition, between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” In 2024, that pit is pretty full: a burning planet, extreme weather, the threat of fascism, rampant book-banning, the increasing reliance on A.I., numerous armed conflicts, the continuing menace of nukes, the inevitability of another plague. These all sound like plot ideas from one of the show’s brainstorming sessions. In fact, most were. We have become The Twilight Zone.

Schumer begins his book, of course, with the visionary behind it all, Rodman Edward Serling, who he “firmly places in the 20th Century pantheon of great American-Jewish-humanist-liberal writers and storytellers.…” A WWII vet who’d seen action in the Philippines, Serling got his creative start, via the G.I. Bill, at Ohio’s Antioch University, writing scripts for the campus radio station. The experience soon launched him, in the early ’50s, into television, where he wrote dramas for the live broadcasts of Playhouse 90 and Kraft TV Theatre, both based in New York. Wary of the big city, and of the entertainment world itself, Serling settled in the suburban enclave of Connecticut’s Westport, a tidy community that would become The Twilight Zone’s model for those quiet Maple Streets that get upended by the uncanny. Serling found success there, winning three Emmy Awards in successive years. Those triumphs, Schumer writes, “established Serling, along with peers Reginald Rose and Paddy Chayefsky (who would later do their best-known work in films) as a new commodity on the cultural scene: a television playwright.”

Sometimes smoking, Sterling stood there like an offbeat priest delivering the weekly catechism.

Born into a Jewish family, liberal in his views, and prone to nightmares of the war, Serling was increasingly drawn to social issues and humanitarian concerns. But his attempts to address edgier subjects “put him at loggerheads with the censors of the nascent industry, and its de facto censors: TV’s financial sponsors.…” In 1956, for the live Studio One series, Serling was forced to make significant cuts to his Capitol Hill drama, The Arena, eliminating any mention of political parties or actual issues of the day. Afterward, Serling mused that he would have had better luck “had I made it science fiction, set it in the year 2057, and peopled the Senate with robots.” As Schumer writes, “Cue The Twilight Zone theme.”

And so, a year later, fed up with New York, Serling moved to Hollywood and sold his long-contemplated idea for a sci-fi-ish series to CBS. Now he had creative control — and a chance to address (more freely) those social issues. Like Soviet writer Mikhail Bulgakov, who had cloaked his satires of the system with fantasy, most famously in his novel The Master and Margarita, Serling masked his sometimes scornful assessments of American culture with aliens, magic, and the supernatural. For many episodes, his concept of this twilight zone was a censorship-thwarting buffer zone.

The show’s typical formula was one of incongruence: the staging of opposites. Perceptively, Schumer sees this as a latter-day version of Surrealism, repackaged for the television age. “Compare Serling’s original, 1959 voiceover definition of The Twilight Zone,” Schumer writes — light and shadow, science and superstition — “to the definition of Surrealism itself, by its French poet-founder André Breton: Everything leads us to believe that there exists a spot in the mind from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the high and the low, the communicable and incommunicable will cease to appear contradictory.” That “spot in the mind,” Schumer points out, is The Twilight Zone.

Schumer goes further, suggesting that not only had the show’s surreal mood “countered the status quo of television network programming of its time,” but that “Serling’s concept of alternate realities … paved the way for, and influenced, the turbulent Sixties to come.…” If so, then it was Serling’s physical presence that gave the concept an authoritative heft. In the show’s second season, he started materializing on the sets to introduce each story. That crisp, clipped, ominous delivery was now accompanied by a dark-suited man with a tensed mouth, heavy eyebrows, and a crooked tooth. Sometimes smoking, he stood there like an offbeat priest delivering the weekly catechism.

For a different kind of existential dread, try the tragic absurdity (hinting at both Pirandello and Sartre) of “Five Characters in Search of an Exit.”

Five seasons of The Twilight Zone produced 156 episodes, with Serling writing 92. The bulk of Schumer’s book is devoted to discussing what he believes to be the show’s best, categorized under five themes — “science and superstition,” “suburban nightmares,” “a question of identity,” “obsolete man,” and “the time element.” Though he might be a superfan, he isn’t blindly reverential. Acknowledging that the scripts were too often sophomoric or preachy, he states (the italics are his), “over half … are dogs (with even those sub-rated in stratified degrees of ‘dog’)!”

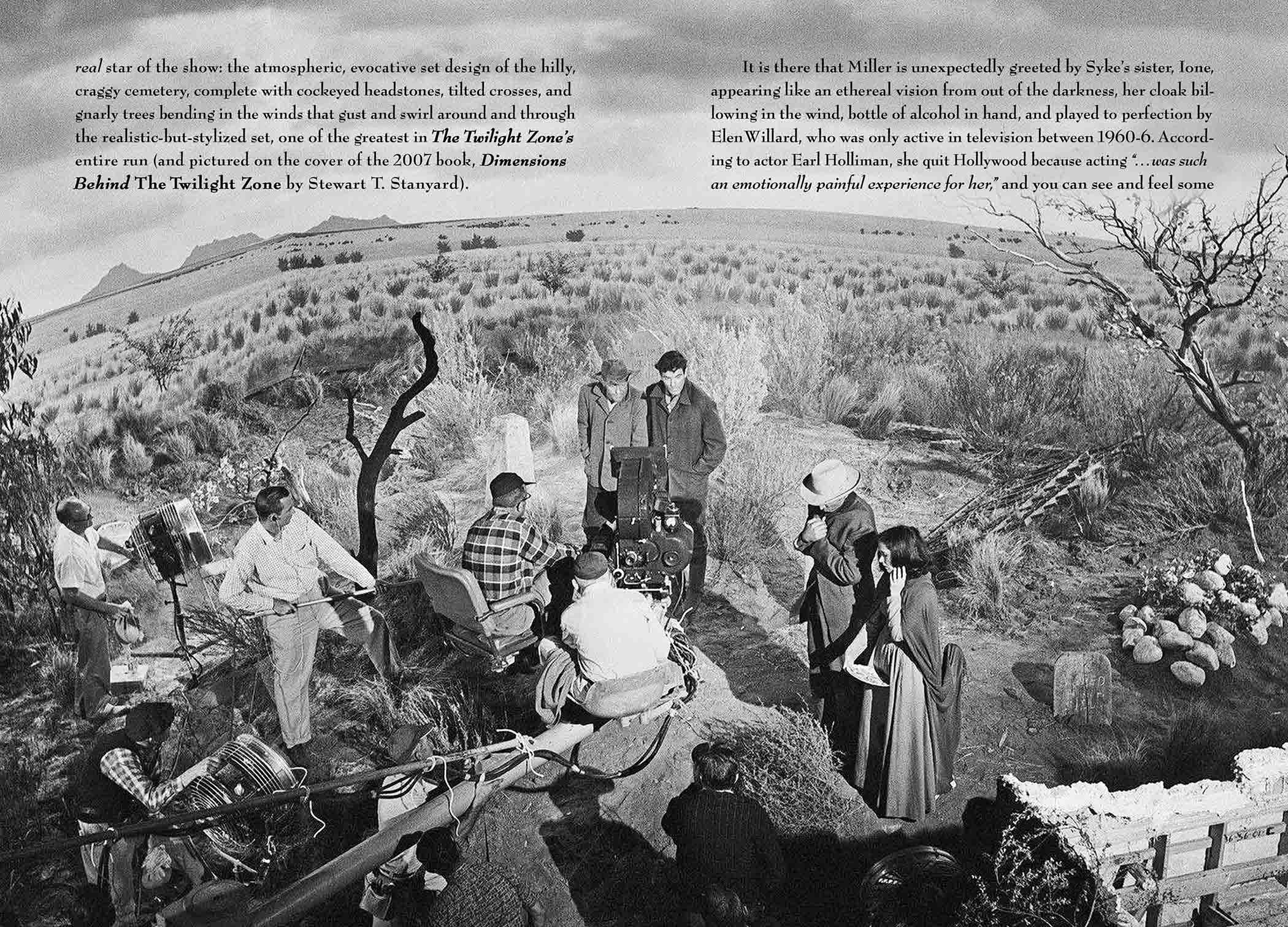

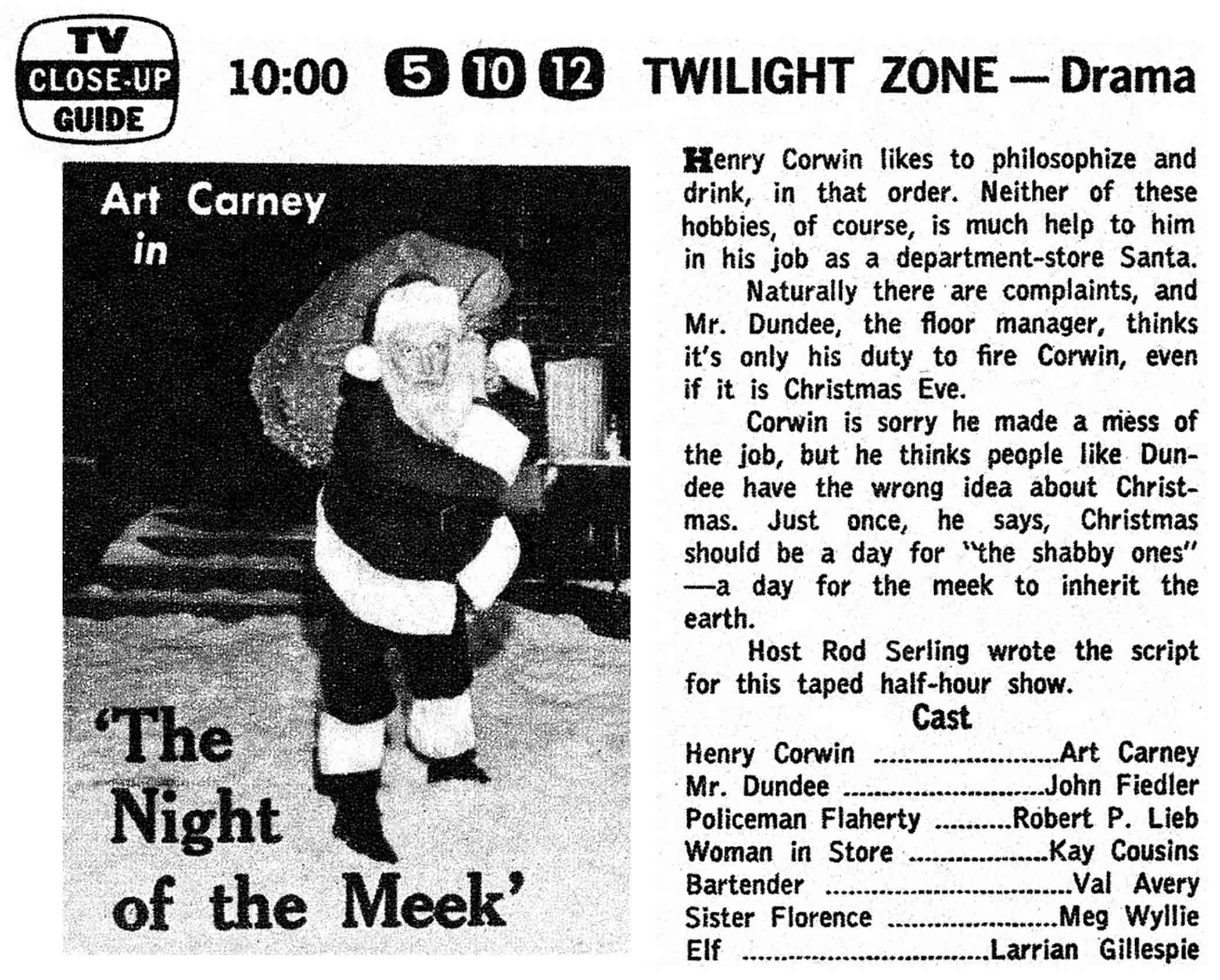

Each selection gets a short essay that runs like a DVD commentary track: a plot summary filled with enlightening remarks on cinematography and soundtrack, production tidbits, historical context, and shout-outs for the actors. Famously, the series featured a parade of future stars: Robert Redford, William Shatner, Elizabeth Montgomery, and Peter Falk, to name only a few.

This isn’t a book you’ll read from cover to cover, especially since Schumer’s style can be a little overwhelming. Possessing both encyclopedic knowledge and enthusiasm, he wants to tell you everything all at once, and often interrupts himself with long parenthetical asides. And because Schumer set the entire book in Bernhard Modern, the font used for The Twilight Zone’s credits, the reading experience isn’t so easy on the eyes.

Still, that enthusiasm carries you along, and will probably inspire viewings of certain episodes, especially those that tap into the current anxious zeitgeist. “The Midnight Sun,” for example — a well-acted drama of “convincing verisimilitude” about deadly climate change, set in 110-degree Manhattan on what Serling calls “the eve of the end.” Or, for a different kind of existential dread, try the tragic absurdity (hinting at both Pirandello and Sartre) of “Five Characters in Search of an Exit,” a story that Schumer says must have seemed to the 1961 audience “like a transmission from outer space.” It plays now like an allegory for pandemic lockdown.

Then there’s “He’s Alive.” Schumer admits that the episode is “heavy-handed,” but it still manages an affective sting, with themes that “ring depressingly familiar.” Featured is a young Dennis Hopper, as Peter Vollmer, a raving neo-Nazi who takes orders from Hitler’s ghost and whips up support for a “free white America” by asking an audience, “Do you want your home infected with the vermin from foreign shores?”

Vollmer dies resisting arrest for murder, but Serling, summing up, warns us that “anyplace where there’s hate, where there’s bigotry, he’s alive. Remember that when he comes to your town.”

Yes, we are The Twilight Zone. ❖

In the Voice’s previous incarnation, Robert Shuster wrote pieces on art, culture, and books. He is the author of the novel “To Zenzi.”