Back in the fall of 2001, the city was still reeling from the 9/11 attacks when workers at the Village Voice heard that one of our own was engaged in her own desperate struggle.

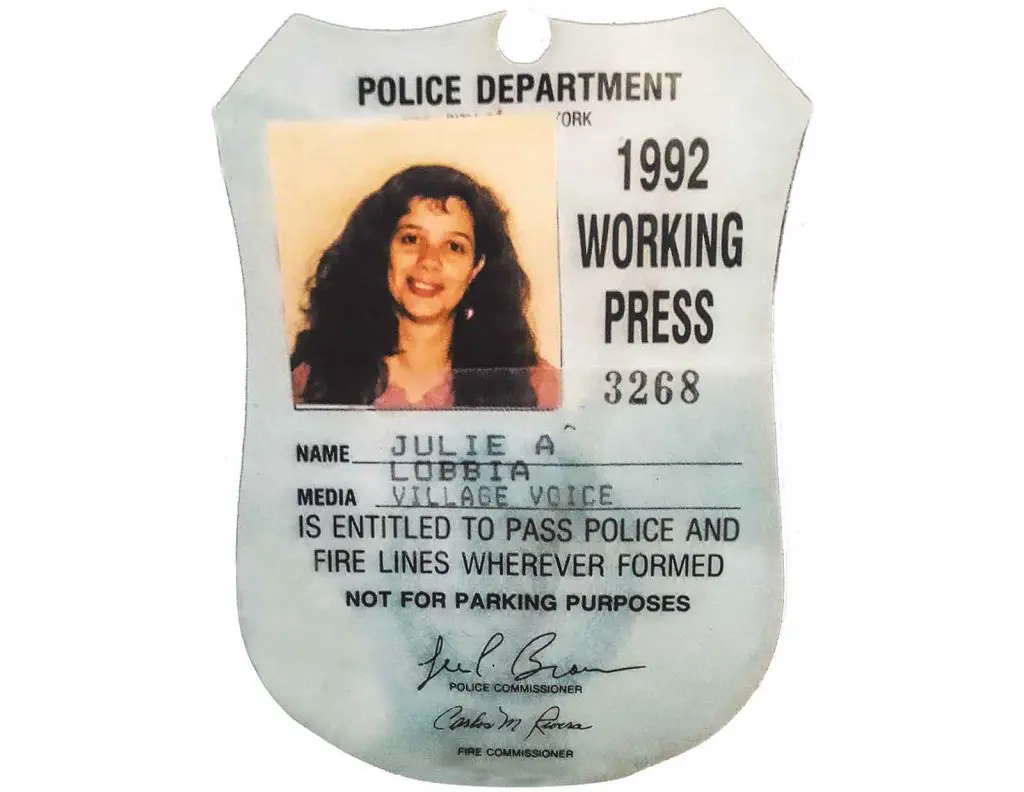

J.A. Lobbia, who wrote the Towers & Tenements column detailing the immoral—when not outright criminal—dealings of crooked landlords and the politicians who enabled them, had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She died a bit more than two months later, on Thanksgiving, at age 43.

So many of those who Julie wrote about and advocated for—the evicted, the homeless, the cheated—as well as the politicians and judges whom she questioned and challenged and demanded more of, along with those who worked with her in the Voice’s rabbit warren cubicles, have never forgotten her.

Below are a few testaments to a journalist who set a bar the rest of us still look up to.

Small Stature, Big Impact

I didn’t like her much at first.

She had caught the eye of my oldest and dearest friend at the Voice, Joe Jesselli, and despite whatever feminist principles I mouthed, I was jealous, and annoyed. Plus she was tiny and exquisite, fearless and intrepid—and given all that, who wanted her around?

In the end, everyone, including me. She married Joe; I didn’t go to the wedding, I am ashamed to say. We made friends slowly, but like so many relationships that get off to a rocky start, our bond ended up being deep and profound, or at least I like to think so.

On the surface, we didn’t have much in common. She was a demon cyclist; I was a clumsy oaf who hadn’t been on a bike since elementary school. I was the fashion editor of the Voice and I loved to shop. Julie was of the if-you-buy-something-you-have-to-give-something-away school of acquisition. She was a serious investigative reporter on the housing beat, with many awards to her credit, dedicating her life to exposing corruption and venality. Though I was the head of the union and cared mightily about the rights of my fellow workers, I have always operated on the Lynnie, you deserve a present! principle to get me through the day.

Which is not to say that Julie didn’t have her own style—she would often change in her office from her bike clothes into one of her trademark thrift store dresses. And she did occasionally let me take her shopping for new things. She may have been saintly, but she was never sanctimonious. We shared a wicked sense of humor. She loved ribald songs—one in particular, which involved a faintly lascivious dance, still makes me laugh.

I remember seeing her coming out of Kmart once, her arms piled high with blankets and pillows she had just bought for an indigent family she had written about. With my usual warmth and tact, I snarled, “Julie, you are not supposed to solve their problems yourself!” “I can do whatever I want!” she shouted back.

What she wanted was to do the most good for the most people in the shockingly short time she had on Earth.

Julie was diagnosed just a few days after 9/11, which only went to prove that tragedy could strike big and small, that no horror is like any other and yet they are all alike in many ways.

Just before she passed away, when she knew that the situation was hopeless, she went for a wild ride without her helmet. I like to think of her that way, speeding down the East River Drive, her beautiful auburn hair streaming behind her.

A little more than a year and a half after she died, one of those commemorative street signs that grace corners in New York City was erected at Herald Square with her name on it. Her mother was at the dedication, and she turned to me and said how nice it was, and I, channeling Julie’s frankness and audacity, replied, “It’s nice, but it sucks.” Her mom, who had the same steadfast intelligence as her daughter, nodded.

“Yes. It sucks.” And it did, and it still does.

—Lynn Yaeger

“No Woman, No Cry”

A Song for Julie Lobbia

Julie Lobbia, unapologetically, was all up in my face the first time we met, one day in 1990. We were newcomers to the Voice, and I was still navigating my way around the maze of shanty-like newsrooms in the paper’s headquarters, at 842 Broadway. It was my fifth visit as a freelancer, after covering Black New York’s reaction, a few months earlier, to the guilty verdicts in the Central Park rape trial, and I got lost working my way back to editor Michael Caruso’s cutting floor. And wouldn’t you know it—I didn’t ask anyone, for fear of ridicule. Oddly, though, I was attracted by a stomping gait that announced the presence of an astonishingly spirited Lobbia, who stood barely five feet tall and gestured wildly with short-bread hands. “Over there!” the stranger with the pretty face instructed, pointing to a room next to a sprawling newspaper morgue, and out of nowhere she began to upbraid me for behaving intemperately toward the sharp-eyed sleuths of the fact-checking department.

She said she’d heard me rattling off answers to a fact-checker’s persistent queries in my sometimes combative Trinidadian brogue. She said she realized the process was still all new to me. I’d better slow down. Be patient. My stories getting into the Voice depended heavily on the fact-checkers’ say-so. And, please, Lobbia added, striking a note of levity as I grimaced, tone it down on those sultry calypsos I’d been belting out while aimlessly milling about the staid workplace. I told her that the song in my head since the verdict was Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry,” a tribute to the grieving mothers of the Central Park Five.

Months later, after the Voice relocated to 36 Cooper Square, my exclusive reportage about the growing Black activist movement around police brutality and social injustice in New York City became a savage bone of contention among some veteran anti–Al Sharpton critics at the paper. Lobbia jumped to my defense, pointing out that it wasn’t easy corralling Black rage—and having access to Black leadership is why the paper hired me in the first place. Her intense critique of my story “Why is Al Sharpton Behaving?” (after the activist had called for a nonviolent response to the white man who stabbed him in the chest) begat a hasty rewrite that would help me prove the naysayers wrong. It shaped the future of the so-called “race beat” at the Voice. Lobbia would go on to edit some of my pieces, assuring them maximum exposure in Metro, the front-of-the-book section later renamed CityState.

Recently, following Eric Adams’s election as the second Black mayor of our city, I reminisced about Lobbia’s earlier predictions concerning his political ambitions. Her keen interest in him proved hauntingly accurate. In February 2001, Lobbia, who was not editing me by that time, pushed for a feature on the outspoken police captain, who was in a rare position of authority for a Black man in the NYPD. After reading a draft I had sent to her touting “Eric Adams for Police Commissioner,” Lobbia said that a couple of lines painting a human picture of him might endear him to white skeptics who otherwise would dismiss the story as a joke. Wasn’t Adams a likable figure who she had heard described somewhere as “the laughing policeman?”

My story was ready for publication in July, and I added these lines with Lobbia in mind: A stocky, clean-cut figure with an imposing stride, the bald-headed Adams is sometimes referred to as “the laughing policeman” because of his ebullient giggle. For weeks after that I didn’t see much of Lobbia around the newsroom, and I found out later that she was sick.

But one afternoon, as the summer of 2001 faded, the sound of Lobbia’s trademark stomping pierced through the keyboard clatter of muckrakers on deadline. “Noel!” she shouted, and kept on pushing her bicycle toward a back office where she’d toiled for many years. A few minutes later, I found Lobbia with film critic J. Hoberman. She leapt into my arms and squeezed. “I have cancer,” she said. “I never imagined I’d be in your arms crying.” I embraced the little darling with a tight hug. She hugged back, even tighter, as if to say, I feel you—and it’s OK. I let go as my tears gushed, and I walked away, singing, “No Woman, No Cry.” I never saw Julie Lobbia again.

—Peter Noel

Hallelujah for an Editor

I believe I met Julie on her first day at the Voice, in 1990. I was a freelance writer, formerly an intern. The paper had just hired a Metro editor, and I followed the buzz off the elevator to the Voice’s equivalent of a water cooler—our receptionist Frank “Frankie Bones” Ruscitti’s desk. And there was Julie, shining in her genuine and enthusiastic way: 5’ 0’’ with a Chicago accent, sparking conversation and welcoming people as they welcomed her. You could tell she was passionate about the paper, about righting wrongs, and couldn’t wait to jump into the fray.

Julie was curious about everything, and had a great eye for the bizarre, if not the salacious. Case in point, the sex life of living prehistoric creatures. Of course horseshoe crab mating season in NYC would make a great story! It seemed silly yet primordial to be on Brooklyn’s Plum Beach with hundreds of these pointy-tailed horny throwbacks on top of each other or slowly inching into position. Julie was such a contrast to those anthropods seemingly frozen in time. Every outing, every exchange with her felt like living life to the fullest. And she was right. She wrote a very entertaining piece.

We were all thrilled when Julie was given more time to write about housing and poverty issues (which eventually led to her column, Towers & Tenements), but it left a big hole for Metro writers. A great editor is like having a better you on the job. One Christmas Eve afternoon I had to be at 36 Cooper Square to work on a housing piece with an editor I didn’t always get along with. But, hallelujah, when I got there it turned out that Julie was my editor. Best Christmas gift ever! On the topic of housing, she was insightful and zealous, occasionally bouncing around in her seat like a shark sensing which way to turn the story to go in for the kill. We worked in the shadow of a small statue of Jesus, arms outstretched, part of Julie’s collection of found objects. And there was her bicycle, always at the ready.

It’s hard to believe she’s been gone so long. I imagine all the good she would have done and the awards she would have won, as well as the things I would have learned from her. She was a true urban hero, riding the city streets, seeking out injustice and enjoying the ride.

—Jill Weiner

Hellacious Rider

She wanted to be buried in her bike shoes.

Julie Lobbia was a mad cyclist. For years, she logged at least 125 miles a week—sometimes far more—running errands, reporting, doing loops of Central Park, and taking long weekend rides. She kept track of the miles she was putting on her new bike frame, a petite one she had grudgingly chosen to suit her height.

I met Julie years after I left my job as copy chief for the Voice, because a mutual friend who worked there, Karen Cook, thought we would hit it off. She was right. We met for dinner, and Julie, in her trademark old-fashioned old-lady wingtip boots, explained that she was skipping her favorite part—red wine—because she had gout. Gout! I was entranced by her throwback ailment, and then bowled over by her racy humor and raucous laugh.

We rode all over New York City, delving into Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens. And with the New York Cycle Club, we sped along in tight, disciplined formations deep into New Jersey and Long Island. Not with the fastest group of cyclists, who were expected to average 23 miles an hour, but with the second-fastest, averaging 21 miles an hour. We could hit 50 or even 60 on a major downhill, and we would ride all day.

How strong and fierce she was. Total energy, intelligence, and grit. I once floated the idea that she had “short woman syndrome,” because, at five feet tall, she could outreport, outwrite, outbike, outlaugh, and outlast pretty much everybody. Everything was more interesting with Julie. She’d make odd connections, tease you. She called us all by our last names, tough-guy style.

On Thanksgiving Day, 2001, just hours after I had seen her last, I got a call telling me she was gone. I wrote a draft of her obituary and we sent it to the New York papers. Somebody questioned that our biking group made three loops of Central Park in under an hour. “That’s like 20 miles an hour,” the skeptic said. “Come on.” Oh, no, I said. We had computers on our bikes, and we tracked our speed obsessively. We averaged 20+.

Julie was fierce on hills. “Hills are your friends,” bikers say; they hone your technique and make you strong. My view: With friends like that, who needs enemies? But Julie darted up, whatever the grade, standing to get all her 100-ish pounds into the pedals and haul ass.

Our first century—100-mile ride—was actually only hers. The route was out to Montauk, at the southeastern tip of Long Island, and Julie took the longest of the organized routes, starting from the Plaza Hotel, across from Central Park. She logged 120 miles that day, all the way to the Montauk Lighthouse. My cousin Tim and I took the train and started 40 or so miles in. We were already beat when she caught up with us, somewhere near the Hamptons—and left us in her dust, no doubt with a juicy taunt lost to time.

We’d packed red wine and frozen steaks in the bags the ride organizers ferried out for us, meant to hold just a change of clothes. We’d booked a cabin near the beach, and we grilled the steaks and guzzled the wine through the starry summer night. She and Tim cracked each other up by emulating old lechers mumbling about wanting “a little sumpin sumpin.” They carried on with it on the bus ride back the next day, and somehow, for real, it just didn’t get old.

One year, we did the self-billed “flattest century,” in the Delmarva Peninsula (which includes most of Delaware and parts of Maryland and Virginia). The start was early, and our hotel’s walls appeared to be engineered to transmit the sound of the coke-fueled bacchanal next door. At 11 p.m., we called the desk and asked if the two couples partying could be urged to cool it. Moments later, we heard their phone ring, and then the slam of the headset and a woman’s defiant voice, in pure New Jersey twang: “We’re not lowd! We’re not lowd!”

We had the front desk put us through to the room, and we assured the woman that she was, indeed, very lowd.

I fell asleep, but Julie didn’t, not until they stopped, around 1:30 in the morning. At dawn, when we staggered out into the parking lot, Julie was struck by evil genius. I can’t remember which one of us actually called the desk, asked for the room, and, when the very same woman picked up, said, “We just wanted you to know what it’s like not to be able to sleep.” Ms. Not Lowd whimpered, “I will nevah stay in this hotel again.” We were so proud of ourselves.

However sleep-deprived, you can’t really be sleepy while biking. Maybe 60 miles in, we saw the famous wild ponies in the area, and Julie, riffing off the road signs, observed that she had “a Chincoteague in my Assateague.” A guy from a group of born-again riders (as advertised on their jerseys) pedaled up and tried to proselytize us. A few miles later, we followed him onto a fairly lengthy, extremely unwelcome stretch of bumpy terrain, and Julie growled quietly, “Where’s your god now?”

No wonder she wanted to be buried in her bike shoes.

And so she was.

—Andrea Kannapell

Who Needs Art?

Well, as I rummage around in my memory, let me also search through the Village Voice archives … and here it is, the first masthead with that enigmatic moniker: J.A. Lobbia, Assistant Features Editor, in the December 18, 1990, issue. Some say that the best gifts come in small packages, and Julie Lobbia, a righteous muckraker from Chicago, was an early Christmas present to Gotham that none of us knew we had coming.

I wasn’t yet a writer in those days—I was a painter with a day job doing paste-up. Laying out both the ads and the editorial columns on the big blue-lined boards was the perfect vocation for a voracious reader, and I soon realized I might want to try my hand at supplying some of the paper’s content. I had gotten to know Julie through discussing labor issues as they related to the paper’s own, always contentious union negotiations as well as in the larger world, and we were in basic agreement that the bosses should find it in their hearts to part with more of their profits for the general good. But I was also hoping to become a successful artist, and Julie would cackle at the ludicrous disconnect between the intrinsic worth of a painting’s materials—canvas, wood stretchers, paint—and the obscene prices that, say, a Warhol Marilyn Monroe diptych would bring at auction. It was Julie’s contention that such frivolous baubles of manufactured desire shouldn’t even exist until every human on Earth had, at minimum, decent shelter and plenty to eat. My arguments about the sheer beauty or challenging concepts or ameliorating humanism of great art would elicit a dismissive shake of her head and a withering comment about some rapacious landlord who also had a vast art collection.

Still, when I did start publishing art reviews in the Voice, Julie, in her eternal generosity, was one of the first writers who got across to me, with her emphasis on fact-checking, concision, and dynamism, that this whole writing thing was going to be damned hard. And not for the faint-hearted. Fact-checking? I’m writing art reviews, for Chrissakes!

But that was the point: All of these words and facts and (hopefully) informed opinions were destined to be ink on paper, grain on microfilm, and—just a glimmer back then—pixels on screens. You’re always writing for posterity, and you owe it to your readers and to history and to yourself (pretty much in that order) to get the facts straight and true. And it was a privilege—one that had to be earned—to have a platform like the Voice where you could put your two cents’ worth in print.

Still, Julie was writing about street-level injustices, exposés of Dickensian landlords who barely maintained their buildings, even while harassing, threatening, and evicting lawful tenants in a never-ending quest to drive up rents—in order, I guess, to buy another painting at Sotheby’s … maybe one I’d written about at some point.

So I was surprised one day when Julie said there was a show at the Whitney that she wanted to see. I leaped at the chance to escort her. Snow was swirling amid a feral wind; it must have been the opening, because I remember we passed a long line of folks bowing hooded heads and hugging each other for warmth as they waited. It was something straight out of Dr. Zhivago, but I had passes from the press office and told her we could saunter right in. She looked back at the huddled masses and said, in all seriousness, that maybe if we waited in line we’d appreciate the art more, since I was the one who always said art was a refuge from ugliness.

I said something about her being on my turf now, and besides, there was plenty of art that challenged the complacency of those who were rich enough to indulge in it, and it’s damn cold and I’m on deadline, so c’mon.

Inside, I tried to interest her in a Pollock here, maybe a Robert Smithson or Eva Hesse there—those wonders of formal experimentation and enrapturing aesthetics—but they garnered at best a polite nod. And then we found it. The artwork Julie Lobbia had trudged through the bitter cold to see: Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. We faced a wall of black-and-white photographs documenting tenement buildings around New York City, rows of banal facades garlanded with fire escapes. Beneath each photo were typewritten sheets covered with facts and figures, block and lot numbers, sales histories, governing regulations: “6 story walk-up old law tenement,” “6 story walk-up new law apt. bld. (1901-20).”

Before I realized that I was looking at the German-born Haacke’s critique of nefarious wealth, a survey of the real estate holdings of Harry Shapolsky, who had many entanglements with the law owing to his ruthless business model, sketchy shell companies, and bribery scandals, Julie had whipped out pencil and paper and was busily scribbling down important facts, straining on tip-toe to lift her maybe-five-foot frame up a bit higher to study the top tier of revelations.

I sighed and went in search of Jasper Johns’s trilevel American flag painting, the rich, luminous encaustic surface seemingly as dense as plutonium.

Much later, when Julie had filled up one of those hip-pocket reporter’s notebooks, we wandered a bit more. As we prepared to take our leave, we passed Kiki Smith’s 1992 Tale, a sculpture of a woman on all fours with a long tail of feces trailing behind her, a “tale,” as it were, of abjection, of bodily absolutes, and of all that we leave behind.

Julie beamed at me, and exclaimed, “Now, that’s art!”

And she was right.

—R.C. Baker

❖❖❖